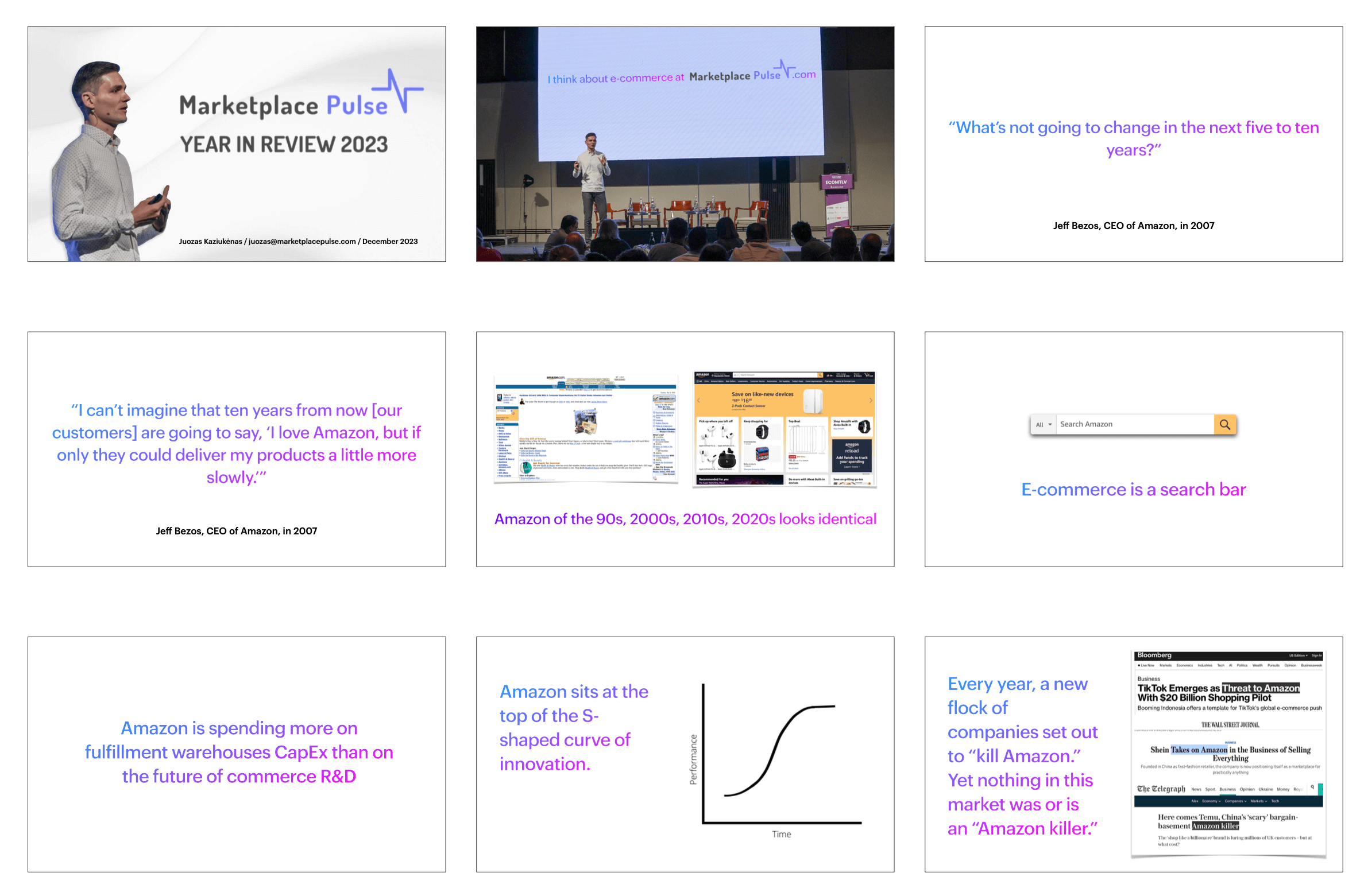

Fifteen years ago, Amazon made a bet that e-commerce is not going to change. That e-commerce of 2007 will still be the future a decade later. As it turns out, it lasted even longer. In October 2007, Harvard Business Review published an interview with Jeff Bezos. In the interview, Jeff Bezos said he often gets asked, “What’s going to change in the next five to ten years?” But he rarely gets asked, “What’s not going to change in the next five to ten years?” He knew that Amazon shoppers want selection, low prices, and fast delivery - and he was confident that won’t change. “I can’t imagine,” he says, “that ten years from now [our customers] are going to say, ‘I love Amazon, but if only they could deliver my products a little more slowly.’“

Answers to “What’s going to change in the next five to ten years?” could have included voice shopping, virtual reality, social commerce, live video shopping, virtual assistants, and more. Today, adding A.I. to the mix seems like a no-brainer. The significance of “What’s not going to change in the next five to ten years?” is two-fold: many new things are transitory, and the fundamentals that support long-term bets are reusable; they don’t become obsolete. Think fulfillment and logistics. Amazon has three key axes covered - selection, low prices, and fast delivery - and it is nearly impossible for the competition to beat Amazon in all of them. Thus, Jeff Bezos confidently said that a shopper uttering, “I love Amazon, but if only they could deliver my products a little more slowly.” is not going to happen.

Jeff Bezos turned out to be correct. “So we know that when we put energy into defect reduction, which reduces our cost structure and thereby allows lower prices, that will be paying us dividends ten years from now. If we keep putting energy into that flywheel, ten years from now it’ll be spinning faster and faster,” he added in the interview. Amazon has doubled in size multiple times since he said that in 2007 - the flywheel did spin faster and faster. It also gained market share, and for a long time, it was the primary driver of U.S. e-commerce growth. To get there, Amazon didn’t reinvent itself repeatedly to keep up with the changing times - quite the opposite. Shopping on Amazon has stayed the same. The website looks the same, the app is the same, and products still come in the same box. E-commerce in the West was a search bar in 2007, and it still is today (that is, most shopping begins and ends by typing a search query).

However, there are more than three axes to e-commerce. “I love Amazon, but if only they could deliver my products a little more slowly” doesn’t exist, but “I love Amazon, but I want to support small businesses” or “I want to pick up items curbside” is common. Some shoppers want to buy locally or buy quality brands, others don’t like the chaotic product selection on Amazon, and more are appalled by frequent stories about how little it pays its warehouse employees. Amazon is a giant steamroller hurrying down a hill, preventing it from noticing and improving things. It is both too fast and too big to stay dynamic. It stubbornly optimizes for selection, low prices, and delivery speed while often missing the rest. Ultimately, the number of Prime members matters the most. As long as they return to Amazon as the default, Amazon is O.K. As Emily Stewart wrote for Vox, “Many Americans like to think of themselves as conscientious consumers — as the types of people who shop their values, support small businesses, and generally try to do the right thing when they buy. We also all live in reality, where people are busy, our funds are limited, and convenience is really nice. Many of us know that buying shampoo at the local pharmacy would be the better option, but it’s 20 minutes away, and what if, once we get there, it’s locked up? So we place an order on Amazon and move on.”

Every year, a new flock of companies set out to “kill Amazon.” A decade ago, it was eBay, then Walmart, then Google. Today, eBay has reduced its ambition to “reinventing the future of e-commerce for enthusiasts,” of which it says it has 16 million. Google killed its shopping marketplace that allowed retailers to sell their products directly on Google this year after it was in limbo for two years. Walmart is the only one that persevered and is especially strong in online grocery. But in general commerce, its online experience is an inspired copy of Amazon.

Some would argue that Amazon keeps its flywheels spinning unfairly and anticompetitively. Others say it is near impossible to steal Amazon shoppers because many are Prime members for whom Amazon is the default. This year, three new challengers are approaching the market with a different take altogether, something Amazon can’t easily squash. Yet nothing in this market was or is an “Amazon killer.” Whatever the reason and future solution for the market where others orbit Amazon like it was the sun, while Amazon stayed the same on the surface, many things inside and around Amazon did change. They were not enough to unseat Amazon from the throne - instead, some made it even more entrenched - but they were changes nonetheless.

Amazon has so little meaningful competition that it doesn’t feel forced to innovate. If Amazon had competitors, they would have pushed it to treat sellers better and invest more in shopping experiments, which would quite likely have led to higher overall e-commerce spending than it is today. That is better for shoppers, sellers, competitors, and even Amazon. Instead, it sits at the top of the S-shaped curve of innovation. There are no obvious next steps to extend the curve, and thus, Amazon is as unlikely to drop to 20% of U.S. e-commerce as it is to capture even more and reach 80%. In mature markets like the U.S., it’s hard to (profitably) offer better prices, more selection, and faster delivery than established players like Amazon.

Contents

- Introduction

- E-Commerce Growth

- Fulfillment Logistics

- Smartphones and Social Commerce

- Made, Sold, and Marketed by China

- Amazon Sellers

- Retail Media Networks (Advertising)

E-commerce Growth

E-commerce spending in the U.S. grew the slowest since the 2009 recession. E-commerce sales grew only 7% and exceeded $1.1 trillion, up from $1 trillion in 2022. And, adjusting for inflation, the actual growth figure is even smaller. E-commerce spending remains bigger than the pre-pandemic forecasts would have suggested. Compared to that theoretical market, where the pandemic didn’t happen, and e-commerce grew at the rate it had grown for years before, e-commerce spending is 14% above the trendline. E-commerce continues to get bigger, even if it has been flat for the past three years as a share of retail. The latter is less important than the fact that more dollars flow through e-commerce every year.

Amazon occupies 40% of U.S. e-commerce spending. But that’s just one of the ways to look at its position. For example, Amazon is 4% of U.S. retail, including all brick-and-mortar stores. Retailers with physical stores feel its impact and competition unevenly. Many could safely ignore Amazon’s presence far away in the distance. That’s different for online retailers acquiring shoppers through the same digital marketing channels Amazon is. Online retailers notice Amazon’s 40% share of e-commerce. There is also a third method: Amazon is 80% of U.S. e-commerce marketplaces. For e-commerce businesses that sell through marketplaces, Amazon is everpresent and unavoidable. Thus, if the conversation is about retail, Amazon could almost be an afterthought. However, e-commerce and marketplaces begin with Amazon.

Not all shopping tends toward large retailers like Amazon; Shopify is the proof. Combined spending on the millions of Shopify stores continues to grow faster than the overall market - annualized GMV surpassed $200 billion this year. One reason is that Shopify continues adding new merchants. Another is that more consumers are comfortable buying directly from brands. Shopify continues to make undecisive experiments transforming its pool of merchants into a marketplace; it launched a web version this year. But the way most shopping happens on Shopify remains to be brands driving shoppers to their stores through advertising. Thus, Shopify is closer to QuickBooks than Amazon - it powers e-commerce stores and doesn’t create demand. It got further away from Amazon when it abandoned its fulfillment bet - Shopify Fulfillment Network - this year. Given the gravitational pull of Amazon, it is significant that the alternative business model to selling on Amazon remains viable for small businesses.

Fulfillment Logistics

Amazon will deliver 5.9 billion packages in the U.S. in 2023, based on Amazon’s internal projections obtained by the Wall Street Journal. It wasn’t until 2018 that it delivered a billion packages in a year. In 2020, it did more than three billion packages. In 2023, it will do nearly six billion, and for the first time, it will deliver more packages than FedEx and UPS. Amazon made no deliveries itself - thousands of small businesses work as Amazon Delivery Partners and employ hundreds of thousands of drivers. They drive Amazon-branded trucks and delivered billions of packages this year. However, plenty of them have complained about operating conditions and pay, “We were treated like robots,” Ted Johnson said in an interview with Bloomberg. “They’re so data-driven they don’t know how to treat people with dignity and respect.”

“Amazon is testing delivering packages using drones,” CEO Jeff Bezos said on the CBS TV news show 60 Minutes in December 2013. The service, called Amazon Prime Air, promised to deliver packages in 30 minutes or less using small, uncrewed aircraft. But it wasn’t until 2020, seven years later, when Amazon won Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) approval to operate its fleet of Prime Air delivery drones. “This certification is an important step forward for Prime Air and indicates the FAA’s confidence in Amazon’s operating and safety procedures for an autonomous drone delivery service that will one day deliver packages to our customers around the world,” David Carbon, vice president of Prime Air, said in a statement then. By 2022, Amazon was still only testing with a small set of roughly 1,000 selected customers. “The new test flights are part of Amazon’s plan to reach at least 12,000 total trial flights by the end of the year [2022], the documents say. Of the 12,000 flights, Amazon expects roughly 5,000 to be commercial flights for trial customers, with the other 7,000 being run for separate durability and reliability testing,” wrote Eugene Kim and Katherine Long for Insider. Federal regulators bar Amazon’s drones from flying over people, roads, or buildings.

“One day, Prime Air vehicles will be as normal as seeing mail trucks on the road today,” Amazon said in 2013. Amazon Prime Air vehicles - drones - are still rare, but in 2013, seeing Amazon mail trucks on the road was rare, too. And now they are everywhere, along with Amazon planes and container ships full of Amazon-branded containers. Amazon’s drone announcement was a head fake. Because, for all the attention it got, it diverted from the building of unconquerable fulfillment infrastructure. The thousands of packages delivered by drones are effectively zero compared to the billions delivered by trucks.

Fulfillment and logistics are the foundation of Amazon because Amazon doesn’t sell goods. It sells goods that ship in one to two days and, for some shoppers, same-day. The logistics are as much part of the product as the products themselves. Amazon has spent the last two decades building warehouses and investing in fulfillment infrastructure to deliver more goods to more zip codes faster. It has trained shoppers that infinite selection combined with fast delivery is the model for online shopping. Fulfillment is not the cost center or unavoidable business unit - it is what Amazon sells.

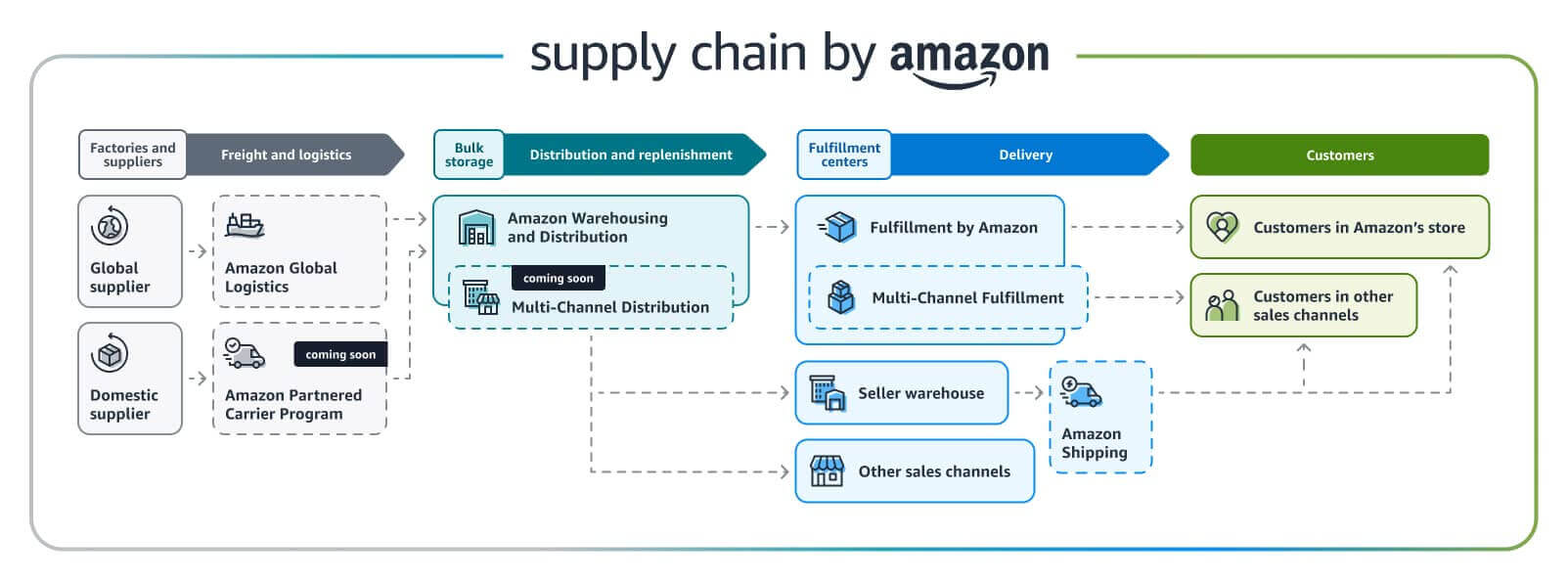

But Amazon can’t make everyone shop on Amazon. So, it is trying to be the retail infrastructure even when shopping happens elsewhere. This year, it introduced Supply Chain by Amazon, a collection of existing physical and online services and some new changes. It’s an end-to-end solution that handles the product’s journey from when it leaves the manufacturer to when the shopper receives it. The most significant change is opening it up to power non-Amazon sales channels. Previously, its logistics and fulfillment services predominantly served Amazon sellers to sell on Amazon.

Supply Chain by Amazon consists of three layers. First, services to import goods from factories and local suppliers. Second, a warehousing solution to store those goods and supply them for sale on Amazon, other sales channels, and physical stores. Last is fulfillment on Amazon through FBA and other channels through MCF and Buy with Prime. Before this year, the warehousing solution (Amazon Warehousing Distribution) would only resupply FBA. That one change transformed this from Amazon-specific to omnichannel. Amazon now runs two-tiered warehousing. The first tier is Amazon Warehousing Distribution (AWD), which was introduced in 2022. It is for long-term storage and is meant to resupply fulfillment warehouses. The second is Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA), which was both for warehousing and fulfillment when launched in 2006 but, over time, morphed into exclusively fulfillment as Amazon pushed for faster inventory turnover.

Without the massive fulfillment warehouse infrastructure to match Amazon’s, Walmart is solving it using stores. Because Walmart has stores within 10 miles of approximately 90% of the population in the U.S., it can use them as pickup points and for store-fulfilled delivery. “50% of the items that we sell online right now are fulfilled out of one of our stores,” said John David Rainey, CFO at Walmart, in an interview with Fortune, sharing the stat for the first time. “It’s convenient for the customer, but also good for us because the most expensive part of delivery in e-commerce is the last mile. We’re able to reduce the amount of mileage that we have to travel.” At Morgan Stanley’s retail conference in December, Rainey added, “The most expensive part of delivery is the last mile. That’s where our physical footprint of 4,700 stores in the United States that are within ten miles of 90% of Americans gives us an enormous advantage.”

Walmart is the biggest player in online grocery in the U.S.; hence, a substantial amount of its e-commerce volume comes from online grocery, a category uniquely fit for fulfillment from stores. However, using stores for fulfillment limits the product selection to tens of thousands of items - Walmart has over 100 million products for sale online. That broader catalog ships from its warehouses (including the marketplace because most sellers have their inventory stores in Walmart warehouses). Thus, 50% of their sales are from stores, including grocery and first-party; the other 50% is a mix of marketplace and first-party, and that comes from Walmart warehouses and seller warehouses.

Smartphones and Social Commerce

iPhone launched in 2007. TikTok launched in 2017. Both now feel ubiquitous, but only recently has consumer interaction with the internet exploded in features, reach, use minutes, and more. Smartphones drastically increased the number of people online and accelerated the impact of digital interactions on real-world decisions. For shopping, that meant a shift from logging in to Amazon on a desktop computer to place an order to spending hours scrolling social media feeds and noticing products to buy. Pre-smartphone e-commerce was a sales channel; now, digital drives all retail.

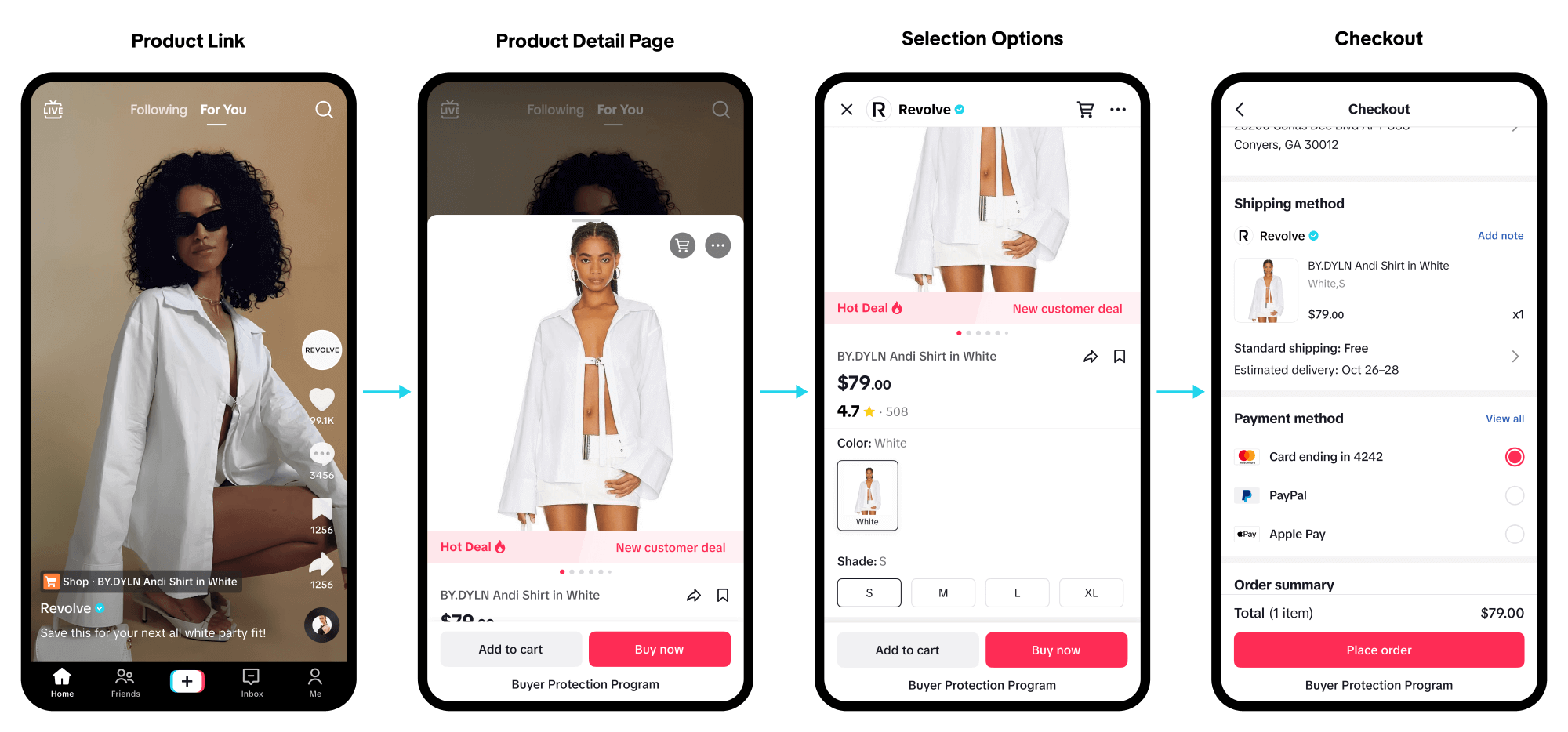

The currency in the post-smartphone age is attention. Social media networks like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok hold most of it. The three biggest social networks significantly influence commerce; however, primarily as ad networks, serving shopping-related ads that link to external e-commerce websites. They’ve tried bringing transactions on-platform for years by implementing native storefronts and checkout features. Those allow shoppers to buy the item tagged by an influencer or featured in an ad without leaving the social app. But that type of checkout remains rare. In April, Facebook announced that Shops on Facebook and Instagram would be required to use Facebook’s checkout, thus ending support for Shops that direct people to an e-commerce website to complete a purchase. The change does not affect ads; they can still link to external websites. In August, The Information reported that TikTok also planned to ban links to external e-commerce websites. Most likely to make space for TikTok Shop.

TikTok Shop is the closest U.S. shoppers had to social commerce at scale. TikTok officially launched its in-app e-commerce platform TikTok Shop in the U.S. in September. What’s unique about TikTok’s approach is its willingness to go all-in. “We have a very aggressive plan to make a splash in the industry and make sure that people out there understand that TikTok is a place for shopping,” Nico Le Bourgeois, one of two executives overseeing TikTok Shop in the United States, said in an interview with The New York Times. TikTok was also “offering to subsidize discounts of as much as 50% to entice sellers’ participation in its Black Friday program,” according to Bloomberg. Bestsellers on TikTok are not items from established brands, and stores with the most sales volume are not big-box retailers. It is not Away luggage, Glossier makeup, or a retailer like Walmart or Target. Top sellers on TikTok are items that went (and were pushed to go) viral instead. For example, Unbrush Detangling Hair Brush alone sold 700,000 units by the end of the year. Top-selling items on TikTok Shop are already generating over 100,000 sales a month.

TikTok seemingly has a dial to control how much shopping-related content appears in users’ algorithmic feeds. So far, it looked willing to turn that dial further than Facebook and Instagram did. Of course, that has led to some users complaining on Twitter with “tiktok shop has ruined the whole app. it’s all ads and reviews instead of silly little videos” and “Ever since TikTok added the “TikTok shop” everything is just forced overselling of horrible products to earn commission. Like literally every other video… WHERE IS THE DARK HUMOR I CAME HERE FOR????”

TikTok’s ambition is to create a market for social commerce while its competitors like Amazon are undecisive about committing. Amazon has been growing its own take on social shopping through the Inspire feature for a year after launching it in December 2022. It’s a tab inside the Amazon app that reminds of TikTok and offers a swipeable feed of videos and photos promoting various products. But just like Amazon’s many other social experiments, it got lost among the dozens of features Amazon’s app offers. And just like Amazon’s Live, its live-video shopping streaming, the content could be much better. It’s hard to imagine many users tuning in to watch Amazon Live (and audience figures confirm this), and it’s even harder to see them abandoning TikTok for Inspire. Amazon hopes to figure out social commerce before social networks can solve shopping. But its hope is not rooted in action. As a result, TikTok captured all the users’ attention.

TikTok’s shopping funnel is unique. Amazon, Walmart, eBay, and the rest of the shopping marketplaces in the U.S. are well-understood problems with known inputs like advertising spend, conversion rate tracking, listing optimization, and the like. They have the typical discovery, consideration, and purchase funnel. TikTok is none of those things. Nor is it a replacement or competitor to Amazon and the rest. TikTok Shop is a content problem. “Whenever you change the channel, buying patterns change - people do not buy the same in malls as in department stores, nor in department stores as in small shops, and so people do not buy exactly the same things online as they do in supermarkets or malls,” wrote analyst Benedict Evans. People do not buy the same way on TikTok as on Amazon or any other online retailer. They also don’t buy the same things.

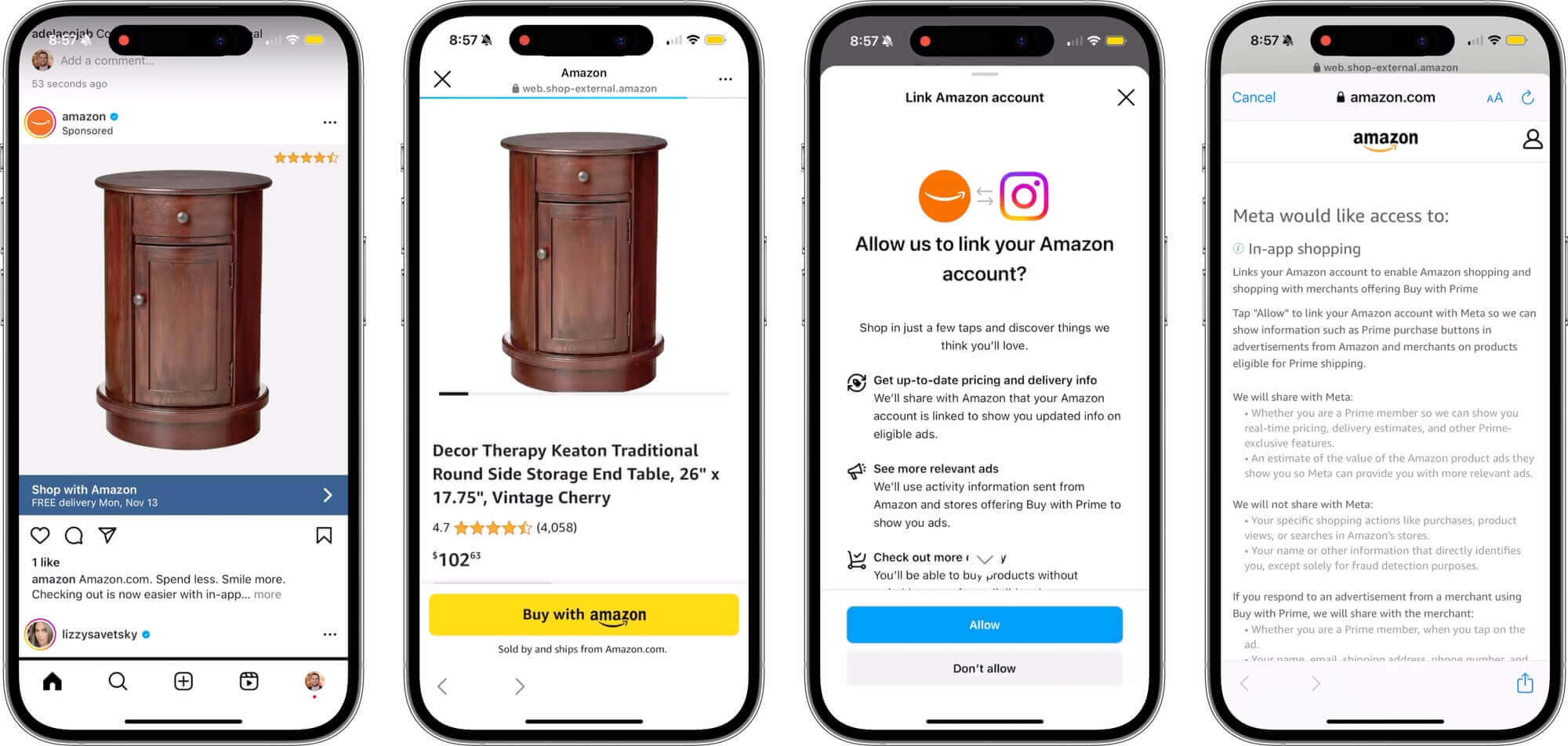

But while its social commerce take failed, Amazon found a different wedge. It partnered with Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram to enable users to link their accounts with Amazon, enabling on-platform commerce and sharing data for ad targeting. Previously, ads on social networks would link to the product page on Amazon’s mobile website, where the user could look at pricing and reviews and ultimately checkout by logging in to their Amazon account. When a user clicks on an Amazon ad now, a stripped-down version of the Amazon product page with a prominent “Buy with Amazon” button loads. This account linking and the new shopping experience is voluntary. Users who opt-in can checkout from the product ad with their saved Amazon payment information and ship to their saved Amazon shipping address. That means fewer clicks before a purchase - it is a one-click checkout on Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat, specifically for Amazon.

TikTok said no, according to The Information. “Late last year, Amazon executives met with their counterparts at TikTok parent ByteDance to propose a novel idea: creating a new advertising format that would let customers buy items from Amazon ads on TikTok without leaving the app, according to a person with direct knowledge of the discussions.” Instead of partnering with Amazon, it birthed TikTok Shop.

Made, Sold, and Marketed by China

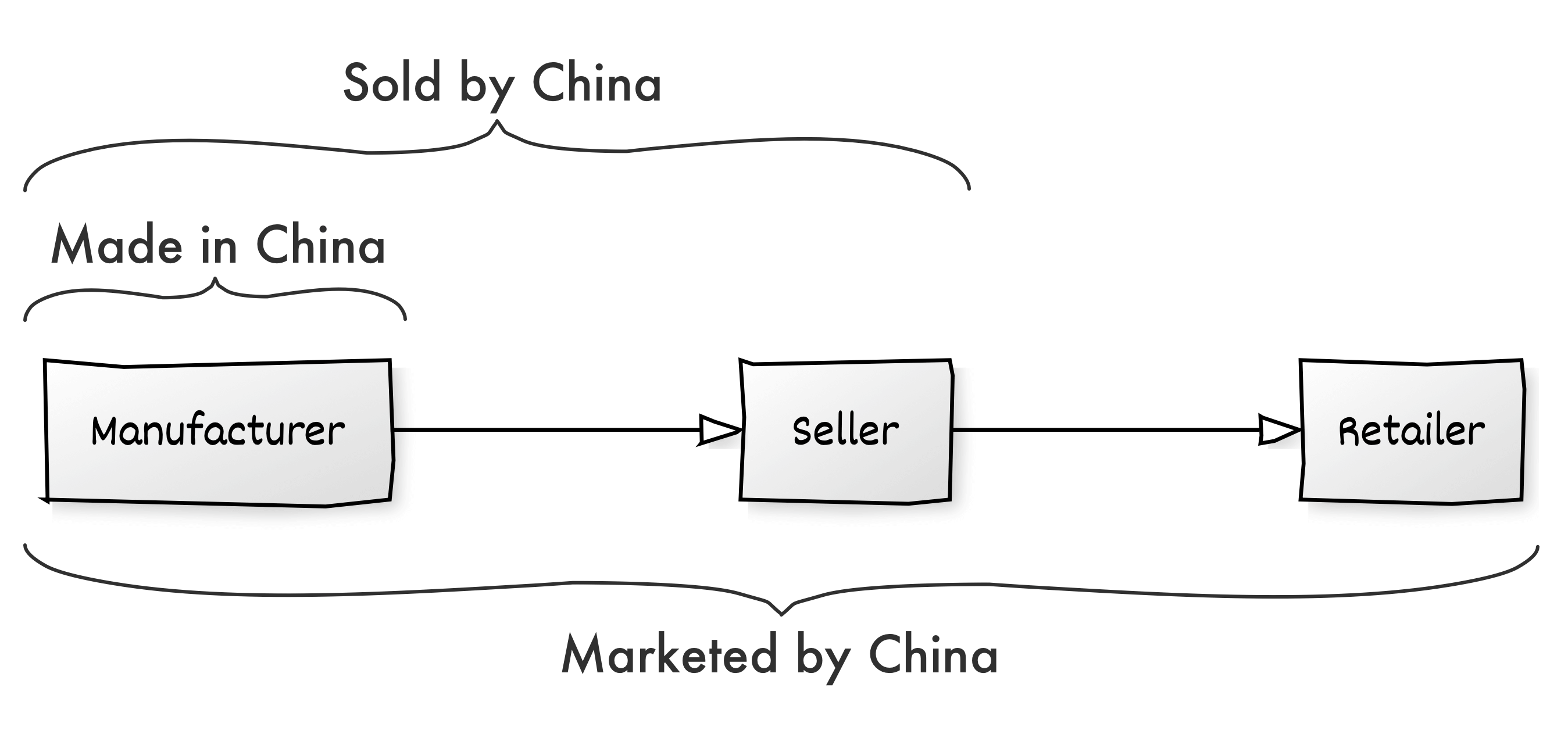

The most noticeable and impactful disruptors are Shein and Temu shopping apps, both from China but only serving shoppers in the West. By the end of the year, they were the No. 1 most-downloaded apps in half of the world’s fifty largest economies. Downloads are not revenue, but downloads indicate ambition. Shein and Temu represent the third iteration of Chinese commerce. The first was “Made in China.” Domestic retailers went to China to outsource manufacturing and cut out domestic manufacturing. Many shoppers didn’t care - or couldn’t afford to care - where goods were manufactured. Second, it was “Sold by China.” Chinese sellers sold through Amazon and took market share from domestic sellers. Their growth was unlocked by Amazon’s fulfillment service, which made the seller’s business location invisible to shoppers. Now, third, “Marketed by China.” Chinese companies are running vertically integrated retailers that are cutting out domestic retailers. The new retailers, Shein, Temu, and whoever will come next, are breaking out of the Amazon sandbox. Factories in China that made products for retailers like Walmart or brands like Nike can now sell them directly to shoppers through platforms built to serve them.

For decades, factories in China made goods that filled the shelves of U.S. retailers and brands. “Made in China, Sold on Amazon” disrupted that model (it didn’t replace it, though - wholesale is still the largest share of China’s exports). Selling on Amazon brought the same benefits Direct-to-consumer (DTC) brought to brands: fewer intermediaries between the shopper and the source of goods. But unlike DTC, sellers on Amazon don’t need to acquire consumers. “One of the themes is Chinese factories who made stuff for Walmart and the likes for the past 20 years now realize they have shot at building a brand themselves and selling directly to the world, without the intermediary… and we are that vehicle.” Wrote Sebastian Gunningham, senior vice president of Amazon Marketplace at the time, in an internal email from 2015 released by the House Judiciary Committee in 2020. In a few years, Amazon became the e-commerce channel for Chinese exports. Today, nearly half of the top third-party sellers on Amazon are based in China.

Since most goods are made in China, it’s unsurprising that most sellers on Amazon come from China. But then it’s also unsurprising that a standalone retailer could be built around them. Before Shein and Temu, there was AliExpress and Wish who tried. The new retailers did it better. Temu has yet to prove itself as it has only been active for a year, but Shein has taken the concept further and bigger than those before it. Shein represents “Marketed by China” because it is a marketing powerhouse with a massive social networking presence rather than a plain catalog offering cheap goods. For example, it has more followers on Instagram than Amazon, Walmart, and AliExpress combined.

Originally a fast-fashion retailer built on consumer-to-manufacturer (C2M) from China, Shein is evolving from a fast-fashion, low-price, slow-delivery retailer to a broad-category retailer to a retailer and marketplace hybrid combining all of the above. To get there, in May, it launched a marketplace and started adding local and international sellers, often with a physical presence in the U.S. As Shein’s head of strategy, Peter Pernot-Day, described in a Modern Retail podcast episode, the marketplace is part of Shein’s localization strategy. “The final piece [of this strategy] is finding both suppliers who make and manufacture Shein clothing, but also third-party sellers who are interested in coming alongside us and reaching our customer base in these local geographies,” he said. However, by the end of the year, most sellers were still from China, so localization has yet to be achieved.

Temu is likely the fastest retailer in history to go from zero to scale, enabled by the parent Pinduoduo’s seemingly unlimited financial backing. It could become the fastest to crash to zero, too. The more than a billion dollars it has spent on marketing so far, and thus its massive operating unprofitability, might spell the end if shoppers don’t stick organically. In just over a year since it launched in the U.S., it added nearly fifty more markets. To reach No. 1, it focused on marketing and gamified referrals to incentivize existing users to invite their friends. It worked - it was the most downloaded app in the U.S. every day of 2023. Temu competes with AliExpress and Wish - just like theirs, its value proposition is very cheap goods that ship in a week or less. It’s less curated or category-focused than Shein. And, unlike Shein, who primarily acts as a retailer and only recently started expanding a marketplace, Temu is only a marketplace (it’s not a pure marketplace but closer to a concession model). That marketplace only hosts Chinese sellers.

Shein and Temu impact everyone who sells online by competing for the same advertising audience or attracting shoppers with cheaper prices. In October, Facebook’s CFO said, “Online commerce and gaming [advertising businesses] benefited from strong spend among advertisers in China reaching customers in other markets.” The best guess is that those advertisers in China were Shein in Temu. In November, Etsy’s CEO said, “I think those two players [Shein and Temu] are almost single-handedly having an impact on the cost of advertising, particularly in some paid channels in Google and in Meta.” Their outsized impact was also visible in the imports data: “A record of more than one billion packages entered the U.S. in the fiscal year ended Sept. 30 under the de minimis exemption - twice the 2019 level,” The Wall Street Journal reported.

Even Amazon couldn’t ignore them. Amazon reacted to Shein by lowering referral fees (transaction fees sellers pay) from 17% to 5% for clothing items priced under $15. For products priced between $15 and $20, it will decrease referral fees from 17% to 10%. Lower fees will allow sellers to lower prices by a few dollars and maintain the same margin. More expensive items remain at 17%. Shein is an order of magnitude smaller than Amazon - its GMV in 2023, which is more than $40 billion, is less than 10% of Amazon’s. But most of that $40 billion is in clothing, which Shein is best known for and strongest in. Its supply chain, tuned to introduce thousands of new designs daily while dynamically adjusting which products get manufactured, is uniquely fit for clothing. It is the biggest online-native clothing retailer.

Shein, Temu, and AliExpress combined now get over 1 billion monthly web visits. Roughly half what Amazon gets in the U.S., but double Walmart’s. Yet, Shein and Temu drive most sales through their apps rather than the website. Hence, even if combined as one, they are an order of magnitude smaller than Amazon in GMV, but they are not small. That’s the market effect Facebook and Etsy executives described.

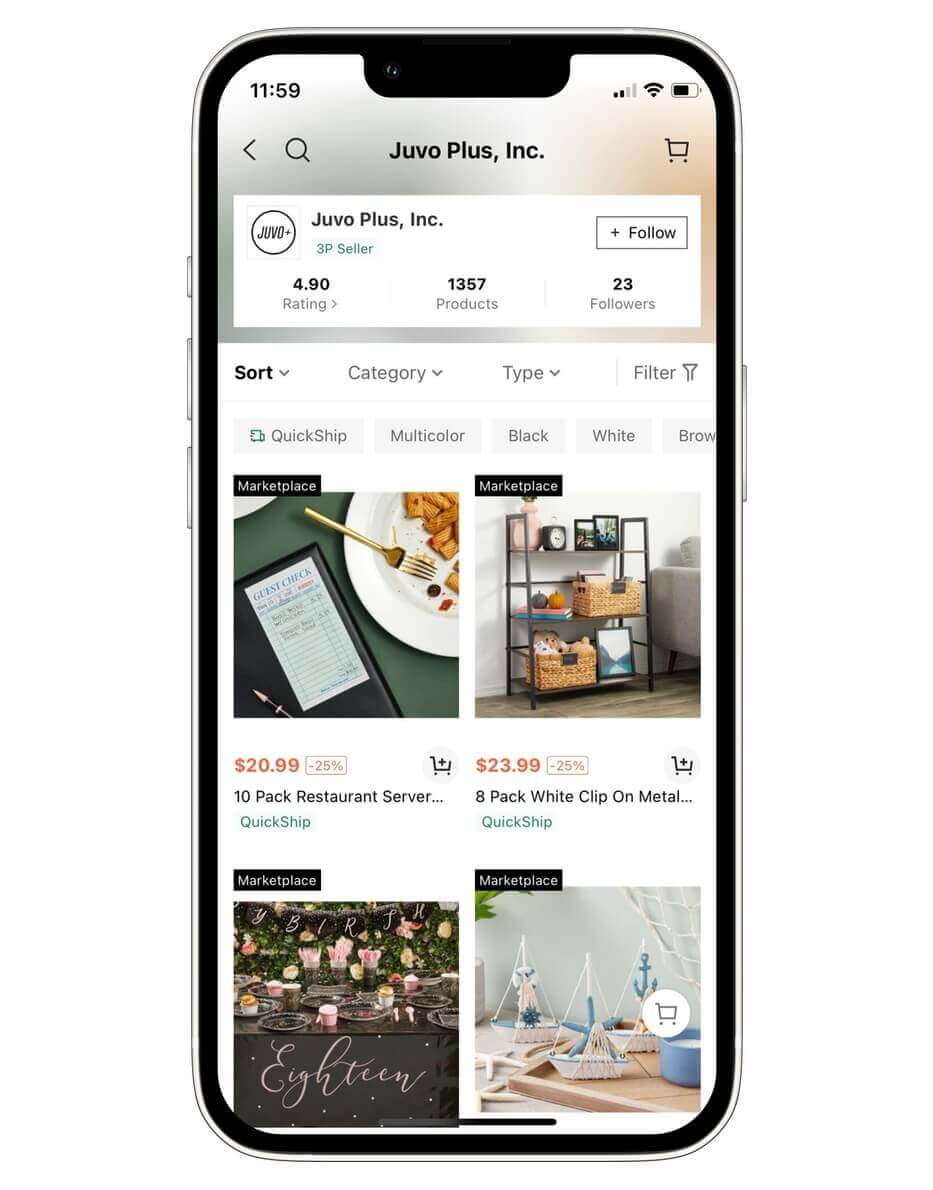

Amazon Sellers

Amazon is its millions of sellers as it continues to move away from 1P sales to 3P sellers. Sellers comprise 60% of overall units sold on Amazon and have an even higher share of GMV. But the shift is gradual. In 2016, the number of products sold through the marketplace exceeded those sold by the retail team. Since then, the marketplace’s share has been growing steadily, albeit with fluctuations in some quarters, often caused by sales events or holidays when Amazon’s retail operation typically plays a more significant role. Over the past eight years - since the marketplace overtook retail sales - sellers have been gaining 150 basis points in market share every year. The shift hadn’t accelerated or slowed, except for 2020, when Amazon struggled to keep its warehouses operational and restricted many sellers from sending in inventory. So far, the shift has appeared controlled and deliberate because it has evolved at a relatively stable rate. Amazon could accelerate it, but it will likely never reduce retail to 0%.

Amazon is pocketing more than 50% of sellers’ revenue, up from 40% five years ago. Sellers are paying more because Amazon has increased fulfillment fees and made spending on advertising unavoidable. According to P&Ls provided by a sample of sellers selling on Amazon.com and using FBA, a typical Amazon seller pays a 15% transaction fee (Amazon calls it a referral fee), 20-35% in Fulfillment by Amazon fees (including storage and other fees), and up to 15% for advertising and promotions on Amazon. The total fees vary depending on the category, product price, size, weight, and the seller’s business model.

The 15% transaction fee has stayed the same for over a decade. It varies by category and can be as low as 8%. Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) fees have steadily increased. Amazon has raised fulfillment fees every year and introduced increases in storage fees. Selling on Amazon is tied to using FBA, so it’s rare for sellers to be successful without using it. Amazon doesn’t set advertising prices, but as more sellers choose to advertise, advertising gets more expensive due to competition. Advertising on Amazon is not optional. Most of the best-converting screen space is allocated to advertising; thus, sellers inevitably have to advertise to have a chance to be discovered. Some sellers still pay very little for advertising, and many resellers spend less than 5% of sales on it, but private label sellers often spend more than 10% on growing their brands.

Amazon describes FBA and advertising as optional services, and by strict definition, they are. However, they are not optional if sellers want to stay competitive and thus succeed. Nonetheless, the fees pay for services that wouldn’t be free elsewhere either. Advertising on Google and Facebook - two major consumer acquisition channels - has also gotten more expensive, and fulfillment services by 3PLs are not always cheaper than FBA. With the launch of Supply Chain by Amazon, Amazon will turn even more of sellers’ costs into revenue. Amazon fees pay for a lot of value; whether they are too costly or have risen too fast is subjective.

Retail Media Networks (Advertising)

Amazon and other retail media networks represent the third wave of digital advertising. Amazon’s advertising business has exceeded a $40 billion annual run rate, growing five times in five years since 2018. Inspired by Amazon, other retailers launched their advertising services. Combined retail media revenues are already almost twice as large as radio and print combined, and the gap with television is closing swiftly, set to surpass it in 2028, according to eMarketer and GroupM. Most of that spending is for programmatic ads that replaced organic placements like products in search results with advertising slots. But the ambition, reach, and data are ever-expanding. For example, during Black Friday, Amazon exclusively streamed an NFL football game for free, which it used to show QR-code-enabled ads personalized to each viewer.

Google and Meta (owners of Facebook and Instagram), known together in the ad industry as the “duopoly,” brought in less than half of all U.S. digital advertising this year for the first time since 2014, when the two reached that status, calculated Insider Intelligence. For a decade, the digital advertising industry was approaching one dominated by the duopoly. Amazon changed that by quickly becoming the third biggest player. Now, with the other retail media networks, digital advertising never had more options. Jerry Dischler, vice president for Google’s advertising products, confirmed that in testimony during the federal antitrust trial against the company, “We are losing share to other new entrants,” including TikTok and Amazon.

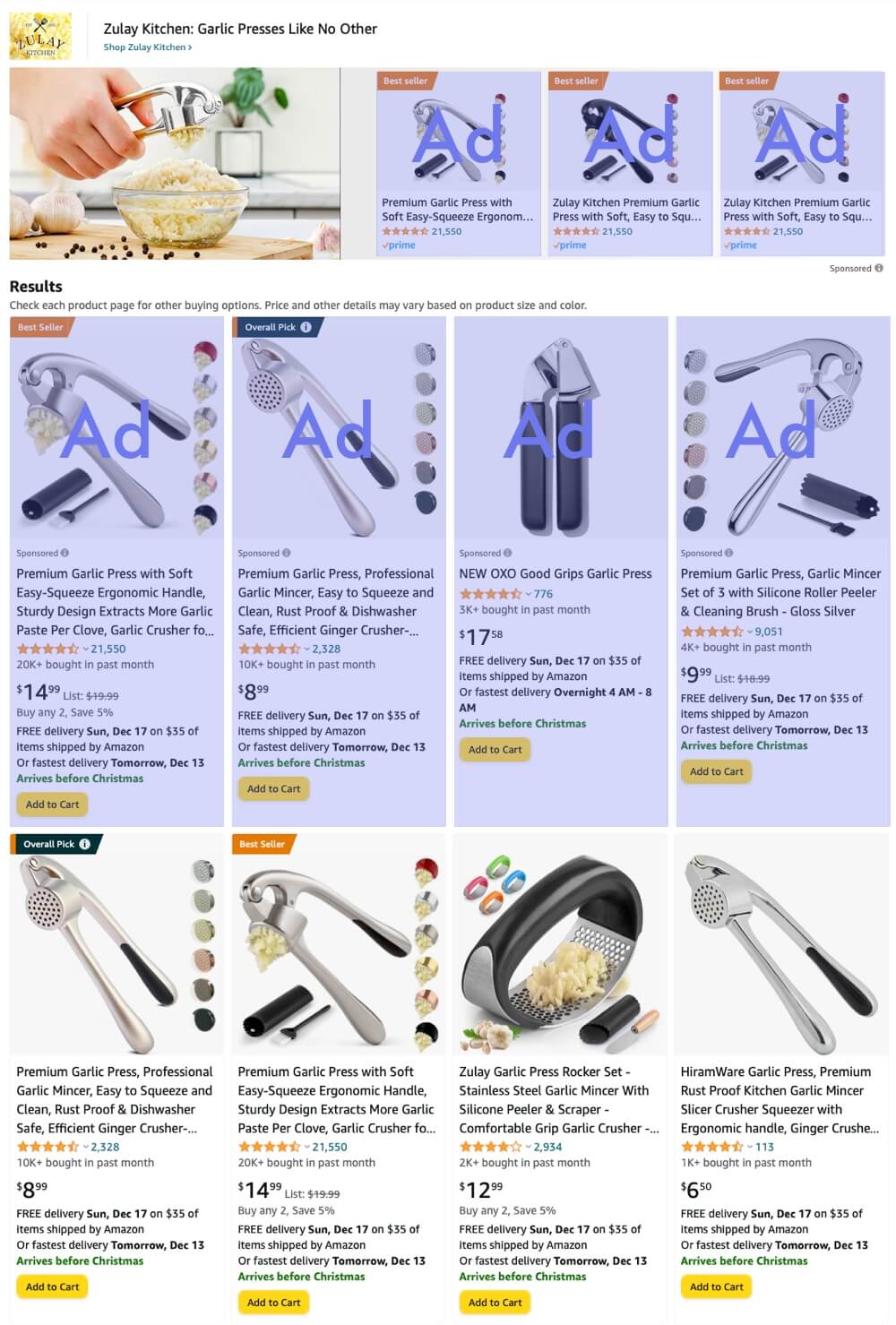

Amazon and other retailers are stuffing their search results pages with ads and replacing recommendation features with sponsored copies to get there. Amazon’s search results page has dozens of ads, most front-loaded towards the top of the page, where often more than half of the products shown are ads. In 2003, then Amazon researchers Greg Linden, Brent Smith, and Jeremy York published a seminal paper called “Amazon.com Recommendations: Item-to-Item Collaborative Filtering.” Then, in 2017, the IEEE Internet Computing journal’s editorial board identified it as best to have withstood the “test of time.” “At Amazon.com, we use recommendation algorithms to personalize the online store for each customer. The store radically changes based on customer interests, showing programming titles to a software engineer and baby toys to a new mother,” read the 2003 paper. However, the functionality described is now absent from Amazon and disappearing from other retailers’ websites. Nonetheless, ads that replaced it are not irrelevant and thus appear native.

Sponsored products among “garlic press” search results on Amazon do not create more demand for the product - they point shoppers to specific advertised products. Thus, brands often pay to sponsor products “just to bring in the same shoppers who were coming anyway,” said Paul Frampton, global president of digital marketing consultancy Control v Exposed, in an interview with The Financial Times. Yet because so many brands and sellers pay to advertise, not advertising means they would steal the sale. Thus, advertising on retail media networks like Amazon is both a tool to launch and grow products and a required part of selling since organic results start far down the page.

Amazon kickstarted the advertising flywheel years ago, which is now not only its most profitable business arm but also one to have transformed how products sell on the platform and how much it costs to sell them. Others are following because “I can’t remember a business with the margin structure of the advertising business here at Walmart,” CEO Doug McMillon said in 2022. In China, Alibaba, which runs some of the largest e-commerce platforms, Tmall and Taobao, makes most of its revenue from advertising because the transaction fees are tiny. Other classified marketplaces follow the same pricing model - only products that advertise have a chance of selling. Amazon is now similar but keeps its relatively high transaction fee.